- Seen in the four significance levels

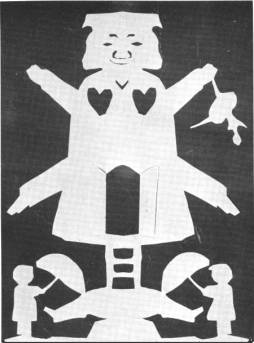

"Mill Man

with dancer and Sandman." Paper Clips by H.C. Andersen reproduced by Kjeld

Heltoft in his book: "H.C. Andersens Billedkunst".

Paper Clips

belonged to Louise Drewsen born Collin. © Kjeld Heltoft and Gyldendal 1969 -

See interpreting later below.

Introduction

The fairy tale "The Windmill" was

printed for the first time in New Tales and Stories, published November 17, 1865,

but there is from Andersen's own hand only a little information about the

actual work of the adventure. "The Windmill" was first mentioned in a

letter of thanks to the Countess Mimi Holstein to Holsteinborg by Skælskør

where Andersen had spent Christmas 1861. The letter is dated January 4, 1862

and includes the following remark: "A new fairy tale turned up, however,

and that the New Year's Day, when I drove from Holsteinsborg; on the road to

Sorø lies a cartwheel, it caught on and an adventure that already looked pretty

on paper are to be seen, leading the name: The Windmill."(Anderseniana

Vol. V, 1937, p. 74). According to this quote, it seems that Andersen had

already started writing the story, and so it is really strange that you do not

hear more about it from Andersen's own hand before the Comments on "Fairy

Tales and Stories" in 1874, in which he writes "There is on the road

between Sorø and Holsteinsborg one cartwheel, I often passed by, it always

seemed as if it would be with in a fairy tale, and it got it, attached to a

piece of creed. This is what I have to add on "The Windmill". (1)

Some might suggest that although the fairy

tale "already so pretty is on paper", it has probably only been about

a synopsis, to maintain the idea. It should probably indicate that Andersen

first mentions the adventure again in 1865 and then in his diary entry for

Friday, June 23: "Ended up, I think the story of the "Golden

Treasure" and read it with "The Windmill" and a few older fairy

tales and stories." Andersen stayed during its annual domestic summer

travel on the estate Frijsenborg near Hammel close to Aarhus. At that time,

both of these fairy tales probably only existed in handwritten manuscript and

maybe in fair copy. In the following time read Andersen both of these fairy

tales at the places, where he was a guest, as in the royal family, King

Christian IX and Queen Louise, at Fredensborg, where Andersen was a guest in

the days 5 to 6 of November 1865, the latter date he notes in his diary:

"The king went into [the town] already at 8 o'clock, I was first then

standing up, drank my coffee and then went to Bournonville, read a few fairy

tales to him; he was completely fascinated by "The Windmill". I told

him that the entire collection was dedicated to him and he kissed me with joy.

[...] "(2)

The Royal. ballet master August

Bournonville was Andersen's personal friends of the same age and so manifestly

and supposedly one of the first, Andersen had read aloud the fairy tale

"The Windmill", which not only liked it, but was even excited about

it. After being retired in October 1861 Bournonville spent his last years in

the peaceful and rural Fredensborg, north of Copenhagen. It was here that he

was visited by the famous and celebrated fairy tale or story-telling poet, as

in 1865, basked in the admiration of both civil as well as nobles and royal

admirers. But as almost always for Andersen, he was rarely undivided happy and

pleased with himself and his surroundings, except when he stayed in manors

large park-like gardens or in the wild. Our Lord's great outdoors was, as he

himself put it, his favourite church, of which he found peace and felt his God

near. See here for example. The fairy tale "The Bell" (1845), where

"the poor boy with the wooden shoes" (an image of Andersen himself)

and the king’s son (a picture of his friend and mentor Hans Christian Ørsted)

their own way to the final meet in the best interests of the God-given great

nature. (3)

But when the fairy tale "The

Windmill" is included here, it’s mainly because this fairy tale, in

addition to being Andersen's personal confession of faith in reincarnation, is

also an allegory of the relationship between the immortal soul and the

perishable body, and also a piece of depth psychology. In this context, the

speaking mill is a picture of human genital double-poled psyche, and the key

words are "Mutter ... she is my soft mind. The old man is my hard; they

are two and yet one, they also call each other "my half part" -. For

Andersen himself was that about "my half womanliness," as he put it

in a letter of September 24, 1833, to his friend Edvard Collin. The term can

partly be seen as an allusion to the comedy writer Aristophanes' description of

human nature, as he puts it in Plato's writing "Symposium". (4)

The fairy

tale "The Windmill" seen in the 1st. significance level

In its literal sense, the fairy tale

"The Windmill" be about a Dutch model of a windmill on a hilltop. But

exactly this mill has the property that it can talk, why it presents and

characterises itself, and that is including this one, which makes its history

into a fairy tale:

There stood on

the hill one cartwheel, proud to look at and proud too:

"Absolutely proud I am," said he, "but I am very enlightened

without and within. Sun and moon, I for external use and for inward too, and

then I also have candles, oil lamp and tallow candle; I dare say that I'm

enlightened; I am a thinking being, and so well that it is a pleasure. I have a

good grinder in the chest, I have four wings, and they sit outside my head,

just under the cap; birds have only two wings and carry them on their backs. I

am a Dutchman by birth, it can be seen on my template; A Flying Dutchman; they

are considered supernatural, I know, and yet I am quite natural. I have a

gallery on the stomach and living room beneath; that's where my thoughts are

housed. My strongest thought, whom rules and reigns, called by others The Man

in the mill. He knows what he wants, he stands over the meal and grits, but he

has his mate, and she’s called Mutter; she is the heart layer; She does not run

backwards, for she knows what she wants, she knows what she can, she is gentle

as a zephyr, she's strong as a storm; she knows how to pry, to get her way. She

is my soft temper, father is my hard; they are two and yet one, they also call

each other "my half". They have toddlers the two: young thoughts that

could grow. The little ones make a fuss! The other day, when I profundity let

"the Old Man" and his men look grinder and wheel after in my chest, I

wanted to know what was the matter, for there was something wrong inside me,

and one should examine himself, so did the small ones a terrible track that

does not take itself out, when you, like me, are high on the hill; you must

remember that you are standing in lighting: the reputation is also lighting.

[...] (5)

Like this initiate the mill its own

history, whose point are that there are alien thoughts to the outside,

impulses, that have led to the mill has changed and the "Old Man" apparent

has changed half and got an even more loving mate with a milder and softer

mind, the bitter disappeared. It was a pure delight. But the years pass,

however, "always ahead of clarity and joy," but the mill knew that

the time would come when the old mill body had been aged and worn out and had

to be demolished. The mill, however, was optimistic, so he thought to himself:

[...] I must be

pulled down to get up as a new and better, I must stop and yet continue to be!

Become quite different and yet the same! It's difficult for me to understand,

however enlightened I am, by sun, moon, candle, oil lamp and tallow candle! My

old timber and masonry shall rise again from the dust. I would hope if I keep

the old ideas: Man at the mill, Mutter, large and small, the family, for I call

it all one and yet so many, all of the thoughts Company, because I cannot do

without! And myself, I have to be, with the grinder in the chest, wings on my

head, the stomach, otherwise I do not know myself, and the others could not recognise

me and say that we have the mill on the hill, proud to see, and yet not

proud."(6)

But the old mill body did not have to be

torn down, before it got that far, it happened one day that caught fire in it

so that it burned to the ground and there was only a heap of dust and ashes

left of it. The fairy tale ends then with the following optimistic statement:

What living who

had been at the mill was, it was not hurt by the event, it won at that.

The miller's family, one soul, many thoughts and only one, got himself a new,

splendid mill, it could be content with, it looked quite like the old one, they

said, there is the mill on the hill, proud to look at! But this was better

designed, more contemporary, because it always goes forward. The old timber that

was worm-eaten and spongy, lay in dust and ashes; the body of the mill did not

rise as it thought; it took it literally, and one should not take everything

just by the words. (7)

The

fairy tale "The Windmill" seen in the 2nd significance plan

The idea of the fairy tale "The

Windmill" is quite simply the one that the individual has an immortal and

thus eternal and essential structure called the soul, and that the part of the

eternal life that takes place in the physical world, is subject to death and reincarnation.

It is expressed with the words "must stop and yet continue to be! Become

quite different and yet the same!" The morality is the culture optimistic

that it is always moving forward, despite the sometimes seemingly is backwards.

It's the same ethos found in the fairy tale "The Flax", 1849, and

therein also expressed in allegorical form.

The optimism on behalf of humanity and

culture did Andersen shared with his friend and mentor, physicist and

philosopher Hans Christian Ørsted. This inspired Andersen to some of his

poetry, which deals with inventions and scientific and technical progress. But

just as important was Ørsted’s natural philosophical influence on the poet

friend, for it was by him, Andersen learned to think with his mind and reason,

and also to use the intellect in religious matters, just as it was by him,

Andersen has got the perception of the soul’s moral development travel through

space. (8)

In the fairy tale’s ending turns Andersen

itself indirectly against the dogmatic Christian concept in general and the

dogma of resurrection of the flesh (the body) on Judgement Day in particular.

This is discussed in the following sections:

The

fairy tale "The Windmill" seen in the 3rd significance level

As initially mentioned, Andersen mentions

"The Windmill" the first time in a letter of thanks to the Countess

Mimi Holstein to Holsteinborg by Skælskør where Andersen had spent Christmas

1861. The letter is dated January 4, 1862, and includes the following remark:

"A new fairy tale turned up, however, and that the New Year's Day, when I

drove from Holsteinsborg; on the road to Sorø lies a cartwheel, it caught on,

and an adventure that already looked pretty on paper are to be seen, leading

the name: The Windmill. "

In the indirect above quote, it was the

aforesaid cartwheel on the hill somewhere between Holsteinborg and Sorø, who

gave the idea and inspiration for the tale to him. However, this was not

unusual, for it was often happened before in his writing career, he found

inspiration for his literary works in real life or in everyday life, as he

supposedly considered "a divine adventure in which we ourselves

live," and as he saw it as his poetic mission to pass on to his fellow

man. (9)

Already in his debut novel "The

Improvisatore" from 1835, Andersen comes in at, from where he get his

inspirations and ideas for literary works. It happens in the novel's second

part of the ninth chapter, entitled "Bringing up. The small Abbess

"in which he talks with the little abbess and including, among other

things says the following:

"Have

you not," I asked, "often in the monastery learned some beautiful

hymn or sacred legend that was put into verse; often, as you least thought upon

it, then is in some cases, an idea emerged from you, by which the memory is

awakened about this or that poem, they have since been able to write it down on

paper; the verse, the rhyme itself, has led you to remember the following, as

the thought, the contents were you clear; so it goes also the Improvisatore and

poet, me at least! Often, I think it's memories, lullabies from another world

that wake up in my soul and as I must repeat."(10)

It is also in a letter dated November 20,

1843, to his friend and colleague B.S. Ingemann that Andersen tells us, from

where he got his inspirations and ideas for his books, including, not least, to

the fairy tales. It happens when discussing his then-latest adventure,

"The Snow Queen" and "Elderberry Mom”, both published in 1844:

[...] - I think, and it will please me if

I'm right; I have come to appreciate to write fairy tales! The first thing I

did, was the most older I had heard as a child and I, by my nature and manner,

retold and re-created; they I originally have created: f. example. The Little

Mermaid, The Storks, The Daisy, etc., however, most won applause and it has

given me the run! Now I tell of my own chest, grab an idea for the elderly -

and then says to the little ones, while I remember that father and mother often

listen to them, and you have to give them a bit of thought! - I have a lot of

subjects, more than to any other poetry art; it is often for me, as every

fence, every little flower said, look at me, and my history go up in you and if

I want it, then I have the story! - (11)

In the "Comments" to Fairy Tales and

Stories", 1874", Andersen writes about the fairy tale "The

Windmill", it is "a piece of creed." This is as previously

discussed above, together with the doubts he since his youth had had on the

dogma of the resurrection, as he actually rejected on the grounds that the idea

of the dead body’s resurrection would solely on the basis of the

laws of nature be a total impossibility. The kind of immortality - even only

for the elected who confessed to Jesus Christ - neither could nor would Andersen

accept as something that could happen in a world where the all-loving God is

prevailing. This view he had acquired during his time in grammar school

1822-27, and he insisted on it the rest of his life.

So far as it has been determined, Andersen primarily found

inspiration for his concept of immortality of the soul in the Neo-Platonic myth

of the soul's fate, on the basis of which he in 1825 wrote the poem "The

Soul". An avid reader of the Bible and especially of the New Testament, he

found moreover also the inspiration for his belief in the soul and its destiny

after death of the physical body especially in Paul's first letter to the

Corinthians, which is especially evident from his poem "Pauli 1 Cor. 15,

42-44 "(1831). It need only to cite the quote by Paul that Andersen has

set over his poem, and only the first of the poem’s in all five verses:

(Notabene! Unfortunately, it is impossible to translate

Danish rhyming poems and other rhyming text directly into English. But in some

cases I still tried a translation without rhyme, but only to do so if and when

the content may be of importance for the understanding of what the relevant

topic is about):

"The body that

dies -" that is sown in corruption,

it rise in

incorruption; it is sown in fragility,

it rise in strength;

it is sown a natural body, it rises

a spiritual

body."

When the earthly land

larva bursts

with its brittle

ribbon,

a spiritual body

encircle

around the strong

spirit;

it is the same forms,

but in a newborn

spring,

and airy, clear and

glorious

the known image

stand. (12)

The quote of Paul is also not quite correctly reproduced

unless the Bible, Andersen has taken advantage of, have had a different

translation of the text. In a recent edition of the Bible's New Testament says

the quote so here added the explanatory verse 41:

"The sun has its

shine, the moon its shine and the stars again their shine:

star differs from

star in glory. So it also is with

the resurrection of

the dead; what is sown in corruption,

rises in incorruption;

what is sown in dishonour, arises in glory;

what is sown in

weakness rises in force; there is sown a physical body,

there rises a

spiritual body. When there is given a mental body

there are also given

a spiritual one."

The theological explanation of the word "soul" is

as follows: The soul is that which lies between carnal (material) and

spiritual, i.e. the natural, by the Spirit of God unaffected human. Otherwise

called the duality of human nature, either with spirit and flesh or soul and

body; spirit and soul is thus used on the higher side of man, flesh and body on

the lower, carnal. See more on this later in the description of the fairy tale

"The Windmill" seen in the 4th significance level.

Additional explanation: In connection with the biblical

concepts of flesh and body, it is important to realise that these

terms are not only pertinent to what we usually mean by "flesh": the

animal meat mass, but also for the living organism, as in the Old Testament

mindset reflects the whole man, so also the soul and spirit. The dualism

between spirit, soul and body, found in Hellenistic philosophy is alien to the

ancient Jewish thought. This is not in the same degree of New Testament’s

conception of the world, where an expression as resurrection of the flesh,

which is to say: resurrection of the body is a concept that is

particularly referred to by Paul (1 Cor. 35-55). But when Paul speaks of the

resurrection of the dead, and including not only on humans but also all

other classes of individuals resurrection, that he believes the resurrection

at the last day, when the last enemy, death, shall be destroyed, and here

cover the situation upon which he, among other things says: "[...] we

must all be changed, in an instant, in a moment when the last trumpet sounds;

for the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible

[indestructible], and we shall be changed. For this corruptible [perishable

body] must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality. So when

this corruptible shall have put on incorruption, and this mortal shall have put

on immortality, then the saying that is written: "Death is swallowed up in

victory." "Death, where is thy victory? Death, where is thy sting?

"[...]. (13)

Seen on the background of Martinus' cosmic analyses, then

correspond what Paul here refers to as “the resurrection", to "the

great birth" to "cosmic consciousness", which means the

situation that the individual's consciousness has been giving permanent access

to God's primary consciousness and not least to God's own knowledge and wisdom.

This is when the individual has been totally transformed since the perishable

will have put on the imperishable, and the mortal put on immortality, and

victory over death and darkness has won. This situation, according to Martinus,

gradually occur for more and more people concerned over the next three thousand

years, except that only after three thousand years later, the vast majority of

people will have achieved cosmic consciousness. But mind you, not as something

automatic, but as something they have earned through their ethical and moral

development, leading to the practice of charity as a natural and of course kind

of mental attitude and practical behaviour.

The fairy tale "The Windmill" is then partly

facing the Christian dogmatic belief in the resurrection, which Andersen

expresses in and with the following statements:

"The old timber

that was worm-eaten and spongy, lay in dust and ashes; the body of the mill did

not rise as it thought; it took it literally, and one should not take

everything just by the words. "(14)

This means that you should not take everything - in this

case the claim or the dogma of the resurrection - literally, that is literally

after the words. In the Collin's and Drewsen's family that Andersen consorted

with fairly often, they were Orthodox Christians, not least applied to Ingeborg

Drewsen, born Collin and her daughter, Jonna Stampe, born Drewsen. That the two

brave women in the Christian dogmas also firmly believed in the resurrection on

Judgement Day, when Christ came on the clouds of heaven, to judge the living

and the dead and separate the sheeps from the bucks, Andersen has actually

given a direct expression of in its diary for Tuesday, March 3, 1868, although

it is simply only referred to Ingeborg Drewsen:

Went out in Rosenvænget when the streetcar was filled up; near come in conflict

with Ingeborg Drewsen, but turned off when she can not bear to get excited, she

believes in "the resurrection", I do not. [...] (15)

But Ingeborg Drewsen's daughter, Jonna, was also a dogmatic

devoted Christian, Evidence of partly her and Andersen's correspondence with

one another and also his portrayal of her in the guise of the Jewish girl Esther

in the novel "To be or not to be", 1857, that the daughter Jonna was

not inferior to her dear mother, when it came to assert the Christian dogmas

bears witness especially a note, probably from around 1850 in the part of

Andersen’s notebook, which was not intended for publication. The situation

described took place in Jonas Collin, the Elder's home in Amaliegade, where in

addition to her daughter Louise Collin also daughter’s daughter Jonna Drewsen

was present. For understanding the problem must the note here be reproduced in

its entirety:

As it the day of C.s

house was talked about "Judas" that in one of my poems had asked his

betrayal of a human, but probably wrong position, Louise, because it concerned

the discussion about the Bible frightened, that the children should hear it. -

Today, when there was talk of Mrs Zytphens madness and I said I already felt

it, when she said to me on the occasion of Ørsted's Spirit in Nature, "yes

he gets second thoughts when the stars of heaven fall down and lie on the

ground like dead leaves!" It's madness. "It has you no right to

say," said Jonna, she has the Bible for themselves and that is it.

"But it is figuratively; otherwise it is madness," I replied,

"every enlightened person knows it is wrong."- No, she went on and

joined herself to the truth of the Bible! I was surprised, affected by this

foolishness that I never would have thought it, and since I could not shout

with Erasmus: The Earth is flak as a pancake, I went home, but much affected. -

(16)

The question or problem about the "resurrection"

was preoccupied Andersen for many years, and especially in the novel "To

be or not to be", in 1857, he settled with the traditional Christian view

of this dogma. It happens in the conversations, the novel's protagonist Niels

Bryde - Andersen's alter ego - has with the Jewish girl Esther - as mentioned

an alter ego for Jonna Stampe, born Drewsen. These interviews are conducted

partly in the novel's second part IV. Chapter: "Goethe's" Faust

"and Esther", and in its Part III. Chapter: "More about

Esther and an old acquaintance, self-searching". During the talks,

especially those dealing with the Christian dogmas, shows Esther alias Jonna

herself as a convinced traditional Christian, defending its positions and the

Christian dogma with great eagerness, but at the same time with the respect, if

not love, she has to her friend Niels Bryde alias Andersen. It with her

respect and clearly loving attitude towards him is abundantly

clear from Andersen’s and Jonna Stampe’s mutual correspondence in real life.

Jonna was 22 years younger than her friend, who had known her since her birth

in 1827, and he came to play an important and even crucial dual role in her

love relationship and engagement with the young Baron Henrik Stampe, who she

married in her 23-year in 1850. A double role, because Andersen in the context experienced one of

its many double infatuations, in which he was in love with both the female and

male party. The difference between this double love and the other double

infatuations, he had seen and been through, probably due to that the female

partner, Jonna, this time in reality and also in deeper and more loving sense

was in love with Andersen. About this witnesses her letters to him and after

his death, for example. to her uncle, Edvard. (17)

As will be clear from what here so far has been said about

Andersen's work, so is this very much based on his personal experiences, like

his own person plays a major role in most of his literary works, whether it

These are plays, poems, fairy tales and stories or novellas, novels and

travelogues. So, in a sense, his entire oeuvre is characterised as a mirror

image of Andersen himself. As we here have noted, makes this relationship also

exists in the context of the fairy tale "The Windmill", although Andersen

herein puts on the guise of a nice cartwheel, which grumble about life in

general and his own life in particular.

One might wonder just why Andersen chose to let a Windmill -

or more accurately a mill man - be the protagonist of a fairy tale, but it is

not so difficult to understand when one considers that Andersen wrote the fairy

tale "The Ice Maiden" the year before he supposedly got the idea for

the fairy tale "The Windmill". "The Ice Maiden" (1861) is

about peasant boy Rudy, who lives in the small Swiss mountain village of

Grindelwald, where he guards the goats and sheep. As an adolescent he goes out

into the world, to learn something, and end up in the Canton Wallis. There he

meets the miller's daughter Babette, with whom he falls in deeply love.

A part of the story takes place in the mill with the miller's family, and it is

an exciting and dramatic story that ends up with Rudy drowning and being taken

over by nature spirit "The Ice Maiden", death’s icy Representative.

But here we merely note that Rudy will visit the mill and he and Babette are

lovers, and that Andersen thus so to speak, had a mill and its family in mind.

(18)

But more importantly, it is perhaps to know and remember

that the mill man walks again especially in Andersen's paper cuttings for both

children and adults. With a little imagination one might think that the mill

looks like a male person. Hans Andersen researcher Johan de Mylius indicate

that the mill man's figure was likely to be a symbol for the open and the whole

person, taking that the figure is both a human, a thing and a son figure, where

the mill wings as four rotating arms are forming the circle. The figure of

Andersen's clip at the top of this article has two hearts and an open entrance

to his home, and at the same time to be a fairy tale figure, the mill also is a

dream figure, which is symbolised by the two symbols of dreams god, in the

shape of two Sandmen’s. The dancer, as the mill in his one is hand holding on

one leg, so she hangs upside down, suggests de Mylius could be a symbol of

love, so that the rotating turbine blades could be seen as symbolic of that

round dance, as love in a sense can be compared to. (19)

However, here I dare attempt to interpret "The Mill

Man" based on Martinus' cosmology, and in that context can the mill as

mentioned also be a symbol or picture on the whole person, while the mill wings

as already mentioned, can be interpreted as a symbol of circuit principle. The

two hearts can be seen as a symbol of the sexual pole principle with its male

sexual pole and feminine sexual pole. The dancer also in this interpretation

can be seen as a symbol of love, while the two Sandmen as well can be

interpreted as, respectively, the masculine dream consciousness and the

feminine dream consciousness. The open door or gate into the mill's body might

symbolise the "open" or perfect man who does not keep anything

hidden, either in its interior or its exterior.

Apart from the above interpretation attempt, then it is prosaic

seen so that many of Andersen's paper cuttings they are often cut out of folded

paper, so the figures get the character of symmetry. This is also the case with

clip "The Mill Man", where the symmetry is observed, apart from the

sprawling dancer, which is probably the clip's original appearance, unless the

'symmetrical' dancer in the clip left side later has been disconnected.

Therefore, it may well be that they here given interpretations of the clip is

not in accordance with Andersen's own perception of it, but this is so far as

known not known.

The fairy tale

"The Windmill" seen in the 4th significance level

Here is the fairy tale "The Windmill" viewed and

analysed in the fourth significance level, i.e. the universal or cosmic plan,

and it can be based on these here established criteria for when a text, in this

case an adventure text can be judged as being cosmic, immediately confirmed

that the fairy tale content meets the criteria no. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. As

far as criterion. 1, it is only the side of this that is termed as the

principle of life units and the organism principle, and which even in just the

last part of this is involved. It is also only the first part of the criterion.

4, namely the spiritual kingdoms or the spiritual worlds that remains to be

discussed directly, whereas the physical kingdoms and the physical world are

clearly implicated. (Re. These criteria please see Appendix at the end of the

notes).

However, one certainly have a right to say that the criteria

no. 2, 3, 5 and 6 are fulfilled to the letter, as the tale’s basic idea is the

soul's immortality and eternal life, including the repeating cycles and

developmental interactions between incarnation and discarnation. But the

overall priority of the sexual pole principle and the sexual pole

transformation is the heart of the fairy tale, which also criterion. 8: the

fate principle and criterion. 9: the cosmic evolution from lower to higher

levels of consciousness is presupposed.

The good mill declares themselves to be "enlightened"

and says of himself:

[...] I am a thinking

being, and so well that it is a pleasure. I have a good grinder in the chest, I

have four wings, and they sit outside my head, just under the cap; birds have

only two wings and carry them on their backs. I am a Dutchman by birth, it can

be seen on my template; A Flying Dutchman; they are considered supernatural, I

know, and yet I am quite natural. I have a gallery on the stomach and living

room beneath; that's where my thoughts live. My strongest thought, whom rules

and reigns, called by others The Man in the mill. He knows what he wants, he

stands over the meal and grits, but he has his mate, and she is called Mutter;

she is the heart layer; She does not run backwards, for she knows what she

wants, she knows what she can, she is gentle as a zephyr, she's strong as a

storm; she knows how to pry, to get her way. She is my soft temper, father is

my hard; they are two and yet one, they also call each other "my half

part". They have toddlers the two, young thoughts that could grow. (20)

The mill can be said to be a symbol of the I, X 1, which is

the upper instance of the subject, and just below is what drives millwork,

namely the wings belonging to the "supernatural" or superphysical,

the high psychic part, X 2, which is consisting of the over-consciousness (with

the therein fitted creative principles of perception and manifestation, and

including the circuit principle and the contrast principle). The gallery on the

stomach and dwelling in the skirt represents X 3, which is the spiritual part,

the psychic organism that is related to the natural, which means the part

consisting of the physical organism. The mill's strongest thought is "the

man at the mill," which here means the male sexual pole, while

"Mutter" is the sexual feminine pole, "they are two and yet one,

they call each other" my half part". Yes, the two sexual poles

represent one half of the whole, which is represented by the sexual pole

principle.

The term "they are two and yet one, they call each other"

my half part" associate involuntarily to the following passage in the

fairy tale "The Snow Queen" (1844), where the two main characters,

the girl Gerda and the boy Kay says: "They were not brother

and sister, but they loved as much of each other as if they were." To

explain how I interpret this phrase, I quote the following paragraph from my

article" Except ye become as little children, ye shall not enter into the

kingdom of God", part 2:

(Quote) Therefore,

when we read the fairy tale "The Snow Queen" with "cosmological

glasses" we see that Andersen let the story take its starting point in a

"paradise" situation and condition ("the childhood home"),

based on that the two sexual polarities ("the two children Kay and

Gerda") works together in the same way and to complete and complement each

other. The masculine pole ("Kay") are equal to the feminine pole

("Gerda"), and therefore their existence are characterised by mutual

love and understanding and harmony with the environment. And that in fact is

that the two poles (again, "the two children") acts as players in a

larger drama of life, is symbolised by the old grandmother, who tells the

adventures and reading from the Bible. She therefore also represents the force,

namely the circuit principle and the contrast principle (alternatively the

principle of hunger and satiation), which starts the line of action. Similar to

Martinus and other 'viewers' knew the wise poet Andersen also that life's

eternal laws, it Martinus calls "the create principles”, periodically

require change and renewal, so that the life experience ability can continue to

be promoted and maintained: the two sexual poles must be separated from each

other ("the two children must each leave childhood environment and staying

away from each other"), to allow the implementation of the vital contrast

formation on which all existence is in fact reliant. (Unquote) (21)

But like everything else in the psychical and physical world

is also the mill subject to its conditions of life, which among other things is

that there are changes to it, in the inner, the psyche, as in the outer, the

physical body. In the mental part rummage all the small and slightly larger

thoughts about everything that the very existence brings with it, and in

particular moments of the fundamental questions of life, such as for Andersen

was God, immortality and justice, and the latter requires and is subject to

reincarnation. In this context it is important to keep in mind that the mill at

one level is Andersen's self-portrayal. The mill must therefore with him

ascertain:

[...] that

"from without also come thoughts and not quite of my family, I do not see

any of it, so far I see no one but myself; but the wingless houses, whose

grinder are not heard, they also have thoughts, they come to my mind and become

engaged to them, as they call it. […] (22)

With the strange thoughts means Andersen probably the

naturalistic, atheistic and materialistic beliefs, which he certainly did not

feel akin to, for they were not of his mind, as opposed hailed the idealistic,

pantheistic and spiritualistic beliefs and values. The people who shared his

spiritualist beliefs were rare; therefore he had to admit that not many of his

peers shared his thoughts and ideas about life and the world. By "the wingless

houses, whose grinder are not heard, they also have thoughts", is Andersen

presumably thinking on people who only do the daily musings about life and the

world. At the time when he wrote the fairy tale "The Windmill", he

was not himself nagged and plagued by its periodic doubt on his life’s cardinal

question: Is the soul immortal and survives with the personal consciousness and

its memories intact? - In the novel "To be or not to be" (1857) he

let its protagonist, Niels Bryde, come to the realisation that "God

exists, but one still necessary in addition to "God" that we could

not do without and that is immortality with consciousness and memory. It's a

need, it is a hope, but that fact can not be proved." - No, as a matter of

fact in the scientific sense, the immortality of the soul is not proved, but in

the fairy tale "The Windmill" confirm Andersen in the form of

religious certainty its belief in the immortality of the soul and in addition:

the belief in physical rebirth or reincarnation, though he did not either here

or in his other writings use the latter word. (23)

But something, which seemed to be of the good, had

eventually changed the mill’s psyche, and that something was the sexual

pole-transformation, which had caused that it like had undergone a rejuvenation

since its second half, the feminine half, had been more loving, softer and

milder, which caused the negative and bitter thoughts and feelings to

disappear. Instead appeared life rather as the great and joyous adventure that

life really was, is and always has been. This experience will only really take

place as the two sexual poles approach each other, i.e., when the hitherto

latent pole grow and develop, and together with the intellectual pole organ,

makes itself increasingly present in influence on the psyche and thus to the

conscious mental life. But the big breakthrough and expansion of consciousness

to the sight to see life in an eternal perspective, occurs only in and with it,

Martinus calls "the great birth". So enlightened was the mill - and

thus Andersen itself - not yet or had not yet experienced, but they felt both

precursor symptoms of this life's big and decisive event:

[...] Strangely enough, yes it is very

weird. Something has come over me or in me; something has changed in the

millwork, it is as if father had changed half part, got an even milder mind, an

even more loving mate, so young and good, and yet the same, but more gentle and

good with time. What was bitter are passed away; it is much more delightful

throughout. [...] (24)

But even if the soul is immortal and live eternally, so do

the regularities of the circuit principle and the contrast principle persist,

which among other things means that the physical body of the mill age and

inevitably goes to meet its death and decomposition. But it did not disturb the

mill, it has now come to clarity about life and themselves, which it expresses

in the following words:

[...] The days go by and the days are always

ahead to clarity and joy, and so, yes it is said and written, so there will be

one day, it's all over with me, and certainly not over; I must be pulled down

to get up as a new and better, I must stop and yet continue to be! be quite

different and yet the same! It's difficult for me to comprehend, however

enlightened I be with sun, moon, candles, oil lamp and tallow candle! My old

timber and masonry shall rise again from the dust. I would hope if I keep the

old ideas: Man at the mill, Mutter, large and small, the family, for I call it

all one and yet so many, all the thought Company, because I cannot do without!

And myself, I have to be, with the grinder in the chest, wings on my head,

balcony on the stomach, otherwise I do not know myself, and the others could

not recognise me and say that we have the mill on the hill, proud to see, and

yet not proud. "(25)

But fate - the law of fate is also true in life - would that

the mill one day had an accident, because there was fire in it and it burned to

the ground and only left a heap of dust and ashes, such as at last the case for

all living creatures, including human beings, regardless of death by accident,

illness or old age, the body stops its functions and die and its solutes pass

into the natural cycle. This does not mean that the living in the being or man,

the soul, dies, on the contrary survive this or that the death of the body and

continues its eternal existence, as in a transitional period is characterised

by reincarnation and discarnation, which Andersen fairy tale "The

Windmill" expresses in the following uplifting and beautiful words:

What living who had been at the mill was,

it was not hurt by the event, it won at it. The miller's family, one soul,

many thoughts and only one, got himself a new, splendid mill, it could be

satisfied with, it looked quite like the old one, so they said, there is the

mill on the hill, proud to look! But this was better designed, more

contemporary, so that is progress. The old timber that was worm-eaten and

spongy, lay in dust and ashes; the body of the mill did not rise as it thought;

it took it literally, and one should not take everything just by words. (26)

This is not an affirmation of faith in the dogma of the

resurrection on Judgement Day, but in short, on conviction of physical rebirth,

in Latin called reincarnation. The conviction should Andersen with his

"pendulum-like mind" - despite occasional doubts and scepticism –

come to confirm several times during his following writings after 1865, right

up to and including his own death 1875. It was particularly in the fairy tale

"Aunty Toothache", in 1872, he once again reaffirmed his belief in

reincarnation, and it happens in the section where the I-protagonist, a young

boy, talks about her aunt, who had a good, now older friend, brewer Rasmussen,

she sometimes was angry at because he always said things straight:

Later she said that it had only been teasing from her old friend; he was the

finest man on Earth, and when he died, he became a little angel of God in

heaven.

I thought a lot about the transformation, and if I would be able to recognise

him in this new guise.

As aunt was young and he also was young, he proposed to her. She hesitated too

long over this, had far too long sitting, was always an old maid, but always a

faithful friend.

And so died brewer Rasmussen.

He was taken to the grave in the most expensive hearse and has great company,

people with orders and in uniform.

My aunt was dressed in mourning and stood at the window with all of us

children, except the little brother, the stork had brought a week ago.

Now the hearse and

the procession passed, the streets empty, aunt would go, but I did not think to

go, I was waiting for the angel, brewer Rasmussen; He had by now become

a small winged child of God, and had to

appear.

"Aunty," I said. "Do not you think that he comes now! or when

the stork again brings us a little brother, he brings us the angel Rasmussen."(27)

So simple, straightforward and childish it may be said that

the reincarnation like birth is one of life's great wonders, especially since

every birth is a rebirth, whether it takes place among men or among animals.

The difference is largely that man consciously can marvel at the miracle of

birth, while those animals can feel instinctive life affirmation. (28)

© March 2012. August 2014 translated into English. Harry

Rasmussen.

____________________________

1. Hans Andersen's Collected Works, Volume 15, C.A. Reitzel Publisher.

Copenhagen 1878 - Countess Holstein Mimi: Mimi Holstein, b. Zahrtmann

(1830-76), daughter of C.C. Zahrtmann (1793-1853), commander, adjutant of King

Christian VIII, the Admiralty 1848-50, commander 1849, Rear Admiral in 1851,

Vice-Admiral 1852. Mimi Zarhtmann was in 1850 married to Count Ludvig

Holstein-Holsteinborg (1815-92), politician and 1870-74 Prime Minister. She was

the sister of the famous painter Kristian Zahrtmann (1843-1917).

2. New Tales and Stories, 2nd Row, 3rd Collection 1865 – the Diary Entry June

23, 1865: Hans Christian Andersen's Diaries, Volume VI, p. 241 - Diary Memo

November 6, 1865: Hans Christian Andersen's Diaries, Volume VI, p. 319, - the

king went already into at 8: This is probably to understand such that the king

in an official capacity went to the residence of the Palace at Amalienborg

Palace in Copenhagen. – Bournonville’s: August Bournonville (1805-79), ballet

master and ballet composer at the Royal. Theatre, married in 1830 with Helene

Bournonville, b. Håkansson (1809-95). The couple had five children: Augusta

Bournonville (1831-1906), a ballet dancer, Charlotte Bournonville (1832-1911),

opera singer at the Royal. Theatre, Edmund Bournonville (1846-1904), physician,

Mathilde Bournonville (1835-90), governess and later teacher, Wilhelmine

Bournonville (1833-1908), adopted daughter.

3.

Bournonville: See August Bournonville: My Theater Life. Memories and

Time images. Volume 2, pp. 160-165. - The fairy tale "The Bell": Dal

and Nielsen II, pp. 204-208.

4. Re. Andersen's letter of Sept. 24,1833 to his friend Edvard Collin, see e.g.

H3-06. Andersen's fourth double-infatuation (2) – His double falling in love

with Edvard Collin and its sister Louise. - Re. Plato: "Symposium",

see e.g. H1-08. Introduction to "The sexual pole principle". See

also. the articles H3-02. Hans Christian Andersen - his personality and

sexuality. A contribution to the understanding of his unique personality, and

H3-02. H.C.ANDERSEN - his alleged homosexuality. The problem seen pros and

cons. In the latter article quoted from comedy writer Aristophanes' speech

about Eros and gender origins and history. – Sorry, but some of these articles

mentioned are so far only available in Danish.

5. Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 195.

6. Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 196.

7.

Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 197. Confer with the fairy tale

"The Flax" (1849): Dal & Nielsen II, pp. 204-208. – Se also the

article: 3.39. The fairy tale “The Flax”

8.

See article: 3.14. Poetry and science - the relationship

between Hans Christian Andersen and the scientist Hans Christian Ørsted. The

article is so far only available in Danish: 3.14. Poesi og videnskab – om

forholdet mellem digteren H.C.Andersen og videnskabsmanden H.C.Ørsted. See also. Harry Rasmussen: H.C. Andersen, H.C. Ørsted and Martinus – a

comparative study. The publisher Cosmological Information 1997. Available only

in Danish.

9. Re. "a divine adventure in which we ourselves live," see the novel

Only a Fiddler, R & R III, p. 128 - Re. "His poetic task", as

Andersen had ever since his youth felt and believed himself as a poet and

writer should be "God's minister". See Diaries I, p. 2. - See also

the essay "Images of the Infinite", R &R VII, p. 9.

10. R & R I, pp. 252-253. - Re. Martinus'

analyzes about the sources of inspiration, see e.g. article 3.01. Fairytale and Cosmology - the adventure genre

in relation to particularly Martinus' Cosmology

11. Kirsten Dreyer: Hans Christian Andersen's correspondence

with Lucie & B. S. Ingemann, letter 95, p. 191. Museum Tusculanum.

University of Copenhagen 1997.

12. H.C. Andersen’s

Collected Works, Volume 15, pp. 245-246.

13. Paul, 1 Cor. 52-55.

14. Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 197.

15. H.C. Andersen's Diaries VIII, p. 31.

16.

H.C. Andersen: "To be or not to be". Novel in three parts, 1857.

R&R V. - Discoveries and Research IX, 1962 H. Topsøe-Jensen: Hans Christian

Andersen Notebooks, p. 165 - "Judas": There must be in the verse

drama Ahasverus, 1847, that Andersen mentions Jesus' disciple Judas Iscariot

with human traits. H.C. Andersen's Collected Works, Volume 11, pp. 549-656. C.

A. Reitzel Publisher. Copenhagen 1878. - Mrs Zytphen: Louise Augusta von

Zytphen, b. Baroness Pechlin (1787-1869)... – H.C. Ørsted: Spirit in Nature:

1st and 2nd Part. Published respectively. 1849 and 1850. Republished in four

editions, the preliminary final in 1978 by Vintens Publishers, Copenhagen, with

the opening of Knud Bjarne Gjesing. In 1851, Andersen published "In

Sweden. A Travel Account", which he in his essay "Poetry's

California" discloses an old noble lady who when she heard about the

infinite and perhaps inhabited starry sky exclaimed: "Is every star a

planet like our Earth, and have kingdoms and courts – how infinite a number of

courts! humans must dizzy!"- R & R, Volume VII, pp.121-122. - The

stars of heaven fall down and lie on the ground like dead leaves!: There must

be a free quote from Revelation, chapter 6, verses 13-14. - Erasmus: Ludvig

Holberg: Erasmus Montanus or Rasmus Berg, Comoedie udi five Acts (1722).

17.

Andersen’s and Jonna Stampe’s, born Drewsen’s correspondence with each other

are mainly printed in Jonna Stampe's eldest daughter, Rigmor Stampe's book:

"H.C. Andersen and his closest Associates". Published by H. Aschehoug

& Co., Copenhagen 1918. - See if necessary also the articles H3-14.

Andersen's seventh double-infatuation (1) - Double infatuation in Henrik Stampe

and his wife Jonna Stampe, born Drewsen, and H3-15. Andersen's seventh

double-infatuation (2) - Double infatuation in Henrik Stampe and his wife Jonna

Stampe, born Drewsen. Unfortunately Rigmor Stampe’s book and the articles

mentioned are NOT yet translated into English. – Sorry, but these articles are

so far only available in Danish.

18.

Dal and Nielsen IV, pp. 121-162. - It should be added that Andersen already in

1830 had written a poem titled "The Windmill on the Hill", but

weather this mill is the mill on the road between Sorø and Holsteinsborg, is

uncertain, as far as can be ascertained, he began first to comment on

Holsteinsborg - and incidentally also the relatively nearby freight Basnæs -

around 1855-56. However, it is conceivable that the poem of 1830 may have

haunted his subconscious when he wrote the fairy tale "The Windmill",

in 1865, I shall now recount the first two verses of the poem’s in all five

verses:

Nota Bene! Unfortunately, it is

impossible to translate Danish rhyming poems and other rhyming text directly

into English. But in some cases I still tried a translation without rhyme, but

only to do so if and when the content may be of importance for the

understanding of what the relevant topic is about.

Our landscape here is

almost flat;

but the moon shines in

the night.

However, what we by

its light have seen,

Is only that

everything goes into one.

In the foreground we

must stay.

There is a bit high

at this place;

The windmill, as we

must pass,

do that we get a

painting.

So merrily all the

wheels now go,

A light one looks

behind the scuttle stand,

And journeyman

carries the bag away;

his comrades are

playing cards,

the beer pot in the

middle of the table stand.

See the millwing,

where it goes!

But between the

clouds the moon laugh,

and distinguished it

all looks.

(In Danish does H. Topsøe-Jensen

reproduce the poem with modern orthography: Hans Christian Andersen’s Poems.

In committee by H. Topsøe-Jensen, pp. 59-60. Publisher Spectrum, Copenhagen

1966)

19. Johan de Mylius: Hans Christian Andersen’s Paper Clips,

p. 26. Komma & Clausen, 1992.

20. Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 195.

21. See article 3.05. "Except ye become as little children, ye shall not

enter the kingdom of God" (II) - the necessity of the 'child

mind'.

22. Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 196.

23. The novel "To be or not to be": R & R,

Volume V, p. 194.

24. Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 196.

25. Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 196.

26. Dal and Nielsen IV, p. 197.

27. Dal and Nielsen V, p. 216.

28.

For the record, it should be noted that in the traditional Bible’s, including

the New Testament’s conception of the world, it does not appear that animals

have a soul. It is probably related to that in the creation story in the first

book of Genesis said that God created man in his image, first Adam, "then

the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground and breathed into his

nostrils, and man became a living being. "(1st Gen. 1,27 and 2,7). This

view, along with the notion that man was set to rule over the animals,

expresses much the view of the animals, which to some extent seems even in the

present. But the perception of animals as inferior human beings and the

resulting disrespectful treatment of these, of course, especially his cause and

explanation of man's own biological origin and evolutionary history. The

biblical concept of the relationship between humans and animals belong to a

later stage culture whose living and understanding the world, we in Europe only

in recent centuries is beginning to leave.

******************

Re. the nine criteria for

what characterises cosmic stories, see below after notes and sources.

Sorry to say, but English

readers must in some cases find the texts in English editions of Andersen’s

Fairy Tales and Stories.

1. Here one can also

refer to the series of Article Collection 3: Articles related to Hans Christian Andersen and his writings

2. Hans Christian Andersen: "Fairy

Tales and Stories", Vol. II, pp. 209-12 in DSL / Reitzel edition

1963-86 by Erik Dal and Erling Nielsen.

3. The

article Thoughts about a waste paper can so far only be read in Danish:

3.33. Tanker omkring en makulatur – om H.C.Andersens

første bog ”Ungdoms-Forsøg”.

4. Hans Christian

Andersen: Collected Works. Fifteenth Vol. Second Edition. Copenhagen. C. A. Reitzel Publisher. 1880, p. 302. Moreover, it is one in itself an

insignificant memorising error from Andersen's side, when he believes that the

tale was written in 1849, it is supposedly written around the beginning of

February 1848. – Re. About Andersen’s occasionally life pessimism, se for

example the article 3.37. The tale of “The Fir-Tree” – Poetic life

pessimism.

5. Dal and Nielsen II, pp. 209-212. The reference also applies to

the following quotes from the fairy tale "The Flax".

6. The preceding text for the

quote reads:

[...] And all the kids in the

house stood around, they would see the flare, they would look into ashes and

see the many red sparks, which, like ran away and vanished, one after the

other, so rapidly - it's the children who go of school, and the very last spark

is the schoolmaster; often they would think he have gone, but then he will come

a little after all the others.

And all the paper lay in a bundle on

the fire. Ugh! Where it broke up in flames. "Ugh!" it said, and just

then, it was a great flame; it went high in the air, as never the Flax had been

able to lift his little blue flower, and shone like the white linen never had

been able to shine; all the written text was for a moment quite red, and the

words and thoughts turned to fire.

7. Hans Christian Ørsted: The Spirit in Nature.

With Introduction by Knud Bjarne Gjesing. The book was originally published in

two volumes hhv.1849-50. Fourth edition: Stjernebøgernes Kulturbibliotek. (The Star

Books Culture Library). The publisher Vinten, 1978. See p. 140. Unfortunately the book is not available in

English.

8. Hans Christian Andersen: A Journey on Foot

from Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager in the years 1828 and 1829. The

book was published originally 2nd New Year's Day 1829. Text Publishing,

Postscript and Notes by Johan de Mylius. Danish classics. Danish Language and

Literary Society. Borgen Publisher, 1986. The quotation is from p. 41.

9. This version of the novel has been reprinted by

H. C. Andersen: Collected Works. Fourth Volume. Second Edition. C. A.

Reitzel Publisher. Copenhagen. 1877. See Part Two, p. 155. The novel has also

been published in Gyldendals Trane Classics in 1970, and herein are the listed

place pp. 140-141.

10. Dal and Nielsen II, pp. 209-212. This

information applies to all the following quotes from the fairy tale.

11. See article 3.38. The fairy tale "The

Windmill" - seen in four significance levels. Re. The fairy

tale Aunty Toothache has not yet been subject for a special article, but

a shorter analysis of it is to be found in my book H.C. Andersen, H.C.

Ørsted and Martinus – a comparative study, 1997, pp. 135-146.

12. See here if necessary. Articles 2.15. The adventurous life cycle (1) - the individual’s

cosmic 'journey' in the involution arch, and 2.16. The adventurous life cycle (2) - the individual’s

cosmic 'journey' in the evolution arch.

13. Re. the cosmic laws, also referred to as create and

experience principles, see e.g. article: Lesson 13: The cosmic creation

principles. Sorry, so far only available in Danish: Lektion 13: De kosmiske skabeprincipper

14. Dal and Nielsen II, pp. 49-76. The article The

Mystery of Life and the childhood Mind could also be read in English in The

Magazine KOSMOS No. 2-2001. See here perhaps. Article 3.32. A cosmic adventure - the fairy tale "The Snow

Queen" (Part 1)

15. Hans Christian Andersen: A Journey on Foot from

Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager in the years 1828 and 1829, the

book was published originally 2nd New Year's Day 1829, Text Publishing,

Postscript and Notes by Johan de Mylius. Danish classics. Danish Language and

Literary Society. Borgen Publisher, 1986, pp. 36-38. – Notice that Martinus

also uses a book as a metaphor for life - including he therefore uses the term

“Livets Bog” ("Book of Life").

© 2014. August 2014 translated into

English. Harry Rasmussen.

******************

9 criteria for what characterises cosmic stories:

To a fairy tale or a story could be described

as cosmic, it is essential that at least one or preferably more of the below

schematic listed items 1-9 included more or less are pronounced in the text:

1. God's existence as him, in whom we live and move and are (the

principle of life units and the organism principle). Note that in the context

of Martinus' cosmology the Godhead is perceived as the highest and ultimate

expression of both male and female. Therefore God also is perceived as the

highest representative of the parents and the protection principle.

2. The immortality of the soul and eternal

life.

3. Eternal life in the form of an

ever-repeating cycle (the spiral cycle), with its days and nights, summers and

winters.

4. The spiritual realms or kingdoms and the

physical realms or kingdoms, or the spiritual world and the physical world.

5. The individual’s developmental alternation between physical and

spiritual life (involution and evolution), or from a cosmic point of view

periodically and alternately stay in God's primary and secondary consciousness.

6. The individual alternates between spiritual and physical

life between lives (reincarnation and discarnation, birth and death).

7. The sexual Pole principle and sexual pole transformation.

8. Karma principle (the law of fate or the

law of retaliation).

9. From the cosmic unconsciousness (cosmic "death") to cosmic

consciousness (cosmic life). Birth pains and the great birth. At this point you

might want to assign the Initiation of three degrees, which are divided and

ritualised in the classic mysteries and some of which also appear in folk

tales’ universe. Here we shall only mention that the three classical degrees of

initiation can also be seen as the psychological factors: 1. The personal

unconscious, 2. The collective unconscious, and 3. The cosmic consciousness and

its cognition and experience that the individual soul is identical with the

world soul, or with the one and universal Deity. This cognition is for example

also fundamental in the Indian monistic identity learns Vedanta, and is

expressed in the words: Atman (individual soul) and Brahman (world soul) are

one. The three classical degrees of initiation can also be translated into

'metal values': 1. Copper, 2. Silver, and 3. Gold. The three classical degrees

of initiation can also be compared with Martinus' description of temple

initiations three phases: 1: The front yard, 2: The sacred temple, and 3: The

holy of holiest.

Re. Mystery initiation’s three degrees,

see The fairy tale "The Tinderbox" - seen and evaluated in four

basic significance: See the section The three basic degrees of

initiation. Very sorry, but that article is not yet translated into

English.

See also: H5-00. The four significance levels in H.C. Andersen's work.

So far only available in Danish: H5-00. De fire tydningsplaner i H.C. Andersens

forfatterskab, og Kosmologien og eventyrene. Se also the article 3.01. Fairytale and Cosmology - the adventure genre

in relation to particularly Martinus' Cosmology

© 2014. August 2014 translated into

English. Harry Rasmussen.

******************